Those who cling to the myth that THC’s role in traffic safety is unclear were buoyed by release in 2017 of guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which stated, “…it is unclear whether marijuana use actually increases the risk of car crashes.”

Those who cling to the myth that THC’s role in traffic safety is unclear were buoyed by release in 2017 of guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which stated, “…it is unclear whether marijuana use actually increases the risk of car crashes.”

https://www.cdc.gov/marijuana/pdf/marijuana-driving-508.pdf

DUID Victim Voices supplied the following analysis to the CDC in December 2020, requesting that the guidance be corrected. Thankfully, the CDC subsequently released a correction. The timing of the corrected guidance indicates to us that our message was unnecessary. They must have already had a revision of their flawed 2017 guidance in development.

https://www.cdc.gov/transportationsafety/pdf/Drug-Impaired-Driving-Summary-Sheet-LD-508.pdf

CDC Marijuana and Public Health informed us January 7, 2021 that “…we plan to post the updated version soon. …we will be removing the prior version.” With a new administration coming in Jan 20, 2021 it remains to be seen if that promise will be kept.

Summary

The 2017 CDC publication “What You Need to Know About Marijuana Use and Driving” is badly flawed and should be recalled for the following reasons:

- The statement “…it is unclear whether marijuana use actually increases the risk of car crashes” is wrong.

- Reasons given in support of the above statement are wrong.

- CDC missed the real reason for the historical confusion over the risk of drug-caused crashes.

Critique of CDC’s Crash statement

It is perfectly clear that THC use increases the risk of car crashes. Some claim there is a lack of clarity based upon the results of poorly-done studies, most of which relied upon NHTSA’s FARS data. NHTSA has cautioned that the drug data in the FARS database cannot be relied upon for those purposes[1].

Alternative methods to demonstrate THC’s role in causing crashes have been conclusive. There are literally thousands of reports on this subject so the references below emphasize meta-analyses, expert panel reviews and recent studies. Methods used to quantify the effect of THC on driving safety include:

These prove THC’s role in causing impairment but do not prove THC’s role in causing crashes which do not occur in laboratory settings.

- On-road driving experiments[6]

These prove THC’s role in causing impairment but do not prove THC’s role in causing crashes because the controls used in the experiments preclude crashes. Because the subjects are observed, they show how THC-impaired drivers can drive rather than how they do drive in actual traffic.

- Simulator studies[7]

These prove THC’s role in causing impairment but do not prove THC’s role in causing crashes since crashes are not possible in a simulator. Because the subjects are observed, they show how THC-impaired drivers can drive rather than how they do drive in actual traffic.

These prove an association but not causation of THC use and crashes.

The best studies in this class provide convincing evidence that THC use increases crash risk. Studies support an Odds Ratio of a crash to be about 2.0 if any THC is recently used. That means the crash risk is double that of a sober driver. Recent studies place the increased risk of traffic fatalities due to marijuana legalization to be in the range of 1.2 to 1.9 additional deaths per Billion Vehicle Miles Traveled each year.[22] [23] [24]

Case-control studies relying upon NHTSA’s FARS drug data provide inconclusive results.

A NHTSA-sponsored 2015 study is frequently mentioned as support by the marijuana lobby that there is no link between THC use and crash risk.[25] [26] The study failed to find a link between THC use and crash risk. Regardless of the media[27] reporting otherwise, that is not the same as finding there is no link. Especially with a study that was not designed to find a link in the first place:

-

- Perhaps due to a limited sample size, the study failed to find a link between crash risk and any drug or drug combination other than alcohol, even though all of the other drugs studied have been shown to have a higher crash risk than that posed by THC.

- Unlike a true epidemiological study, this one did not include observations of all subjects in the study pool, only those who volunteered to be included. It is hard to imagine why a driver knowing he/she was impaired by THC would volunteer to be included, but some did.

- At least 413 of the 3,095 test subjects were innocent victims who were involved in a crash, but did not cause one of the 2,682 crashes.

- The study did not include any freeway crashes. There were only 15 fatalities studied, which limits the usefulness of the study.

- The study locale had a low prevalence of drug use. Only 14.4% compared with a 19-22% prevalence nationally.

These studies also provide convincing evidence that THC impairment increases crash risk.

Unbiased organizations that have reviewed the data conclude that THC use increases crash risk:

- Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment[34] – “There is substantial evidence that recent marijuana use increases the risk of a motor vehicle crash.”

- National Safety Council[35] – Alcohol, Drugs, and Impairment Division – “It is concluded that it is unsafe to operate a vehicle or other complex equipment while under the influence of cannabis, due to the increased risk of death to the operator and the public.”

Critique of CDC’s supporting reasons for their statement

- “An accurate roadside test for drug levels in the body doesn’t exist.”

That is irrelevant. There is no roadside test for alcohol levels that is sufficiently accurate to be admissible in court to prove a violation of DUI per se laws either. Yet we have convincing evidence of alcohol’s role in causing crashes. The alcohol evidence in accepted studies came not from roadside tests but from evidentiary tests on either blood or breath, neither of which is done at the roadside.

- “Marijuana can remain in a user’s system for days or weeks after last use.”

That is not true. Marijuana does not get into a user’s system, much less remain there. It can’t. It’s a plant. Roots, stems, leaves and all. What does get into a users’ system is the chemical constituents of marijuana such as THC. THC doesn’t remain in a user’s blood for weeks unless the user is an addict in which case it’s unlikely that the user would be abstinent for weeks. What does remain in users’ blood for weeks is carboxy-THC, the inactive metabolite of THC. Imprecise language such as was used in the CDC publication add to the confusion of THC’s role in crash initiation, rather than providing clarity.

- “Drivers are not always tested for drug use, especially if they have an illegal blood alcohol concentration level because that is enough evidence for a driving-while-impaired charge.”

Drivers are not always tested for drug use primarily due to cost-driven policies. BAC results are not available for weeks after a blood draw so that cannot be used as the primary reason for not testing for drugs. The lack of drug testing does indeed limit the usefulness of data in FARS, but not as much as the lack of standardization in testing protocols and matrix being tested. A better statement is that drug testing is not commonly done if there is sufficient evidence to convict of DUI-alcohol. Evidence comes not just from BAC levels.

The real reason for historical confusion over the risk of drug-caused crashes

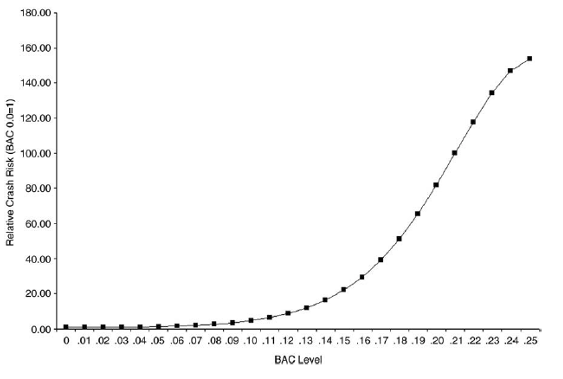

Most crash risk studies of the impact of alcohol impairment on driving relied upon epidemiological analyses that included blood (sometimes breath) testing of both study subjects and controls. Blood testing provides the BAC (Blood Alcohol Content) of the subject. Since both crashes and laboratory tests provide clear objective data points (a crash either did or did not occur compared with gm/dl of alcohol in whole blood or equivalent in breath) it is quite easy to develop statistically significant relationships between BAC and crash risk.

See, for example[36],

Alcohol is an outlier among impairing chemicals because there is a strong and direct relationship between blood levels of the drug (an objective measure) and levels of impairment (a subjective measure). No other drug has been shown to have this relationship. For ∆9-THC it has been proven that such a relationship does not and cannot exist.

That is because blood is never impaired by alcohol, THC, or any other drug. Only the brain is impaired. Alcohol is a small, water-soluble molecule that rapidly establishes a uniform concentration across all highly-perfused organs and tissues in the body. So what is in the blood is in the brain and vice-versa. It is fairly easy to establish the relationship between alcohol use and crashes because there is a strong correlation between blood alcohol levels and levels of alcohol impairment. We can test BAC of drivers to determine alcohol’s role in causing crashes.

That is not true for THC or other fat-soluble drugs. When a large quantity of THC is put into the bloodstream by smoking or vaping, that THC is rapidly absorbed by the brain and other highly-perfused organs and tissues, depleting that THC from the blood. THC remains in the brain, causing impairment. This results in no relationship whatsoever between blood THC levels and either THC levels in the brain or levels of impairment.

Because THC does not behave like alcohol in the body, when the same techniques that were successful to demonstrate alcohol’s role in causing crashes were used for THC, the results were inconsistent.

Many early studies tested for 11-nor-9-carboxy-THC, the inactive metabolite of ∆9-THC. If the relationship between impairment and ∆9-THC is bad, it is even worse for carboxy-THC.

[1] Berning A, Smither DD. Understanding the limitations of drug test information, reporting and testing practices in fatal crashes. NHTSA Traffic Safety Facts Research Note DOT HS 812 072 November 2014

[2] Sewell RA, Poling J, Sofuoglu M. The Effects of Cannabis Compared with Alcohol on Driving. Am J Addict. 2009; 18(3) 185-193

[3] Position on Cannabis (Marijuana) and Driving. National Safety Council. Alcohol, Drugs and Impairment Division. Adopted Feb 12, 2017

[4] Broyd SJ, van Hell HH, Beale C, Yücel M, Solowij N. Acute and Chronic Effects of Cannabinoids on Human Cognition – A Systematic Review. Biological Psychiatry April 1, 2016 79:557-567

[5] Solowij N, Broyd SJ, Beale C, Prick J-A, Greenwood L-m, van Hell H, Suo C, Galettis P, Pai N, Fu S, Croft RJ, Martin JH, and Yücel M (2018) Therapeutic effects of prolonged cannabidiol treatment on psychological symptoms and cognitive function in regular cannabis users: a pragmatic open-label clinical trial, Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research 3:1, 21–34

[6] Hartman RL, Huestis MA. Cannabis Effects on Driving Skills. Clin Chem 59:3 478-492 (2013)

[7] Hartman RL, Brown TL, Milavetz et al. Cannabis effects on driving lateral control with and without alcohol. Drug and Alcohol Dependence Sept 1 2015, 154: 25-37

[8] Gorman T. The Legalization of Marijuana in Colorado: The Impact. Vol 5 Sept 2018. Rocky Mountain High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area

[9] Ramirez, A., Berning, A., Carr, K., Scherer, M., Lacey, J. H., Kelley-Baker, T., & Fisher, D. A. (2016, July). Marijuana, other drugs, and alcohol use by drivers in Washington State (Report No. DOT HS 812 299). Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

[10] Grondel D, Hoff S, Doane D. Marijuana Use, Alcohol Use, and Driving in Washington State. Washington Traffic Safety Commission. April 2018

[11] Li, M-C, Brady, JE, DiMaggio CJ et al. Marijuana Use and Motor Vehicle Crashes. Epidemiologic Reviews. 34:1 65-72

[12] Asbridge M, Hayden JA, Cartwright JL. Acute cannabis consumption and motor vehicle collision risk: systematic review of observational studies and meta-analysis. Brit Med J 2012; 344:e536

[13] https://www.acmt.net/_Library/2015_Forensic_Course/Huestis_-_BW_-ACMTEffectsCannabisDrivingWithWoutAlc12-9-15.pdf.Accesssed 1 Mar 2019

[14] https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13347

[15] Li, Guohua & Brady, Joanne & Chen, Qixuan. (2013). Drug use and fatal motor vehicle crashes: A case-control study. Accident; analysis and prevention. 60C. 205-210.

[16] Chihuri S, Li G, Chen Q. Interaction of marijuana and alcohol on fatal motor vehicle crash risk: a case-control study. Injury Epidemiology (2017) 4:8

[17] Romano E, Torres-Saavedra P, Voas RB, Lacey JH. Drugs and Alcohol: Their Relative Crash Risk. J. Stud Alcohol Drugs. 75 56-64, 2014

[18] Romano E, Torres-Saavedra P, Voas RB, Lacey JH. Marijuana and the Risk of Fatal Car Crashes: What Can We Learn from FARS and NRS Data?. J Primary Prevent (2017) 38:315-328

[19] Santaella-Tenorio J, Mauro CM, Wall MM et al. US Traffic Fatalities, 1985-2014, and Their Relationship to Medical Marijuana Laws. Am J Public Health (2017) 107: 336-342

[20] Aydelotte JD, Brown LH, Luftman KM et al. Crash fatality rates after recreational marijuana legalization in Washington and Colorado. Am J Public Health (Aug 2017) 107 (8) 1329-1331

[21] Armentano P. The influence of cannabis on psychomotor performance and accident risk. NORML 2018 National Conference. Washington DC. July 23, 2018

[22] Aydelotte JD, Mardock AL, Mancheski CA et al. Fatal crashes in the 5 years after recreational marijuana legalization in Colorado and Washington. Accident Analysis and Prevention 132 (2019) 105284

[23] Santaella-Tenorio J, Wheeler-Martin K, DiMaggio CJ et al. Association of Recreational Cannabis Laws in Colorado and Washington State With Changes in Traffic Fatalities, 2005-2017. JAMA Intern Med. Published Online June 22 2020

[24] Kamer RS, Warshafsky S, Kamaer GC. Change in Traffic Fatality Rates in the First 4 States to Legalize Recreational Marijuana. JAMA Intern Med. Published Online June 22, 2020

[25] Lacey JH, Kelley-Baker T, Berning A et al. Drug and Alcohol Crash Risk: A Case-Control Study. Dec 2016 DOT HS 812 355 NHTSA

[26] Compton RP, Berning A. Drug and Alcohol Crash Risk. NHTSA Traffic Safety Facts Research Note DOT HS 812 117 (2015)

[27] https://www.usatoday.com/story/college/2015/02/17/new-study-shows-no-link-between-marijuana-use-and-car-accidents/37400707/ Accessed 1 Mar 2019

[28] Longo MC, Hunter CE, Lokan RJ, White JM, White MA. The prevalence of alcohol, cannabinoids, benzodiazepines and stimulants amongst injured drivers and their role in driver culpability. Accid Anal Prev 32 (2000) 623-632

[29] Drummer O. H., Gerostamoulos J., Batziris H., Chu M., Caplehorn J., Robertson M. D. et al. The involvement of drugs in drivers of motor vehicles killed in Australian road traffic crashes. Accid Anal Prev 2004; 36: 239–48.

[30] Laumon B, Gadegbeku B, Martin JL et al. Cannabis intoxication and fatal road crashes in France: population based case-control study. BMJ 2005 331, 1371

[31] Biecheler MB, Peytvin JF et al. SAM Survey on Drugs and Fatal Accidents. Traffic Injury Prevention 9:11-21 2008

[32] Bédard M, Dubois S, Weaver B. The Impact of Cannabis on Driving. Canadian Journal of Public Health Jan-Feb 2007

[33] Li G, Chihuri S, Brady J. Role of alcohol and marijuana use in the initiation of fatal two-vehicle crashes. Annals of Epidemiology 27 (2017) 342-347

[34] Van Dyke, M et al. Monitoring Health Concerns Related to Marijuana in Colorado: 2018. Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment

[35] Op. cit. National Safety Council

[36] Blomberg RD, Peck, RC, Moskowitz H, Burns M, Fiorentino D. The Long Beach/Fort Lauderdale relative risk study. J Safety Research 40 (2009) 285-292